Supervised Prompt Optimization

Dec 10, 2025

5 mins

The hand-crafted loop everyone knows

Most teams rely on the same hand-crafted loop for prompt engineering. An engineer writes a prompt, tests it on a few examples, notices where it fails, then rewrites parts of the prompt; either manually or with help from another model. This often leads to a new set of failures: sometimes the updated prompt overfits to the new examples and breaks on the old ones, and the cycle repeats. Other times the edits simply don’t help.

Because this process depends so much on intuition and “feel,” the final prompt ends up being more of an art piece than a systematically optimized artifact. And when a new, cheaper model arrives, the cycle usually starts over because the same prompt rarely transfers cleanly across models.

This task is quite time consuming and unforgiving. What if we can do better and formalize this approach? The basis is quite clear i.e. identify failure modes -> update the prompt and so on.

This blog is inspired from the GEPA paper and discusses our learnings and approach to implementing GEPA.

The optimization loop

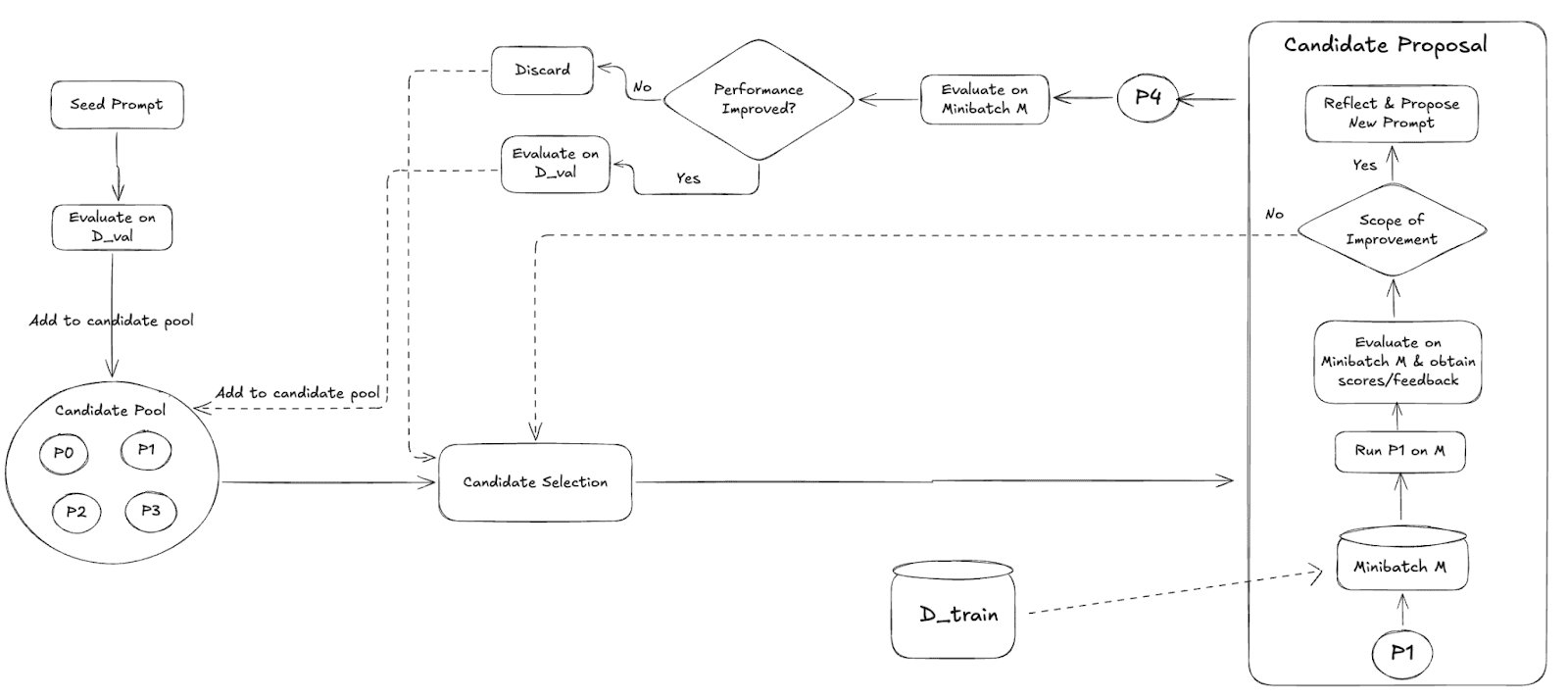

Fig 1: Optimization Loop

The loop starts with a seed prompt. We evaluate this prompt on a validation split and place it in the candidate pool. Each iteration then selects one prompt from this pool using any sampling strategy of our choice and runs it on a minibatch from the training set. This produces two things: the model’s outputs and the judge’s feedback and/or scores.

If the judge signals that the prompt has room for improvement, a refinement step runs. The system reflects on the minibatch traces and proposes a new candidate prompt. This child prompt is first tested on the same minibatch. If its aggregated score beats the parent, we run a full validation-set evaluation and then add the new prompt to the candidate pool. If not, the proposal is discarded.

This cycle continues until the compute budget is exhausted. Over time, the pool evolves toward prompts that perform better under supervised, example-level feedback.

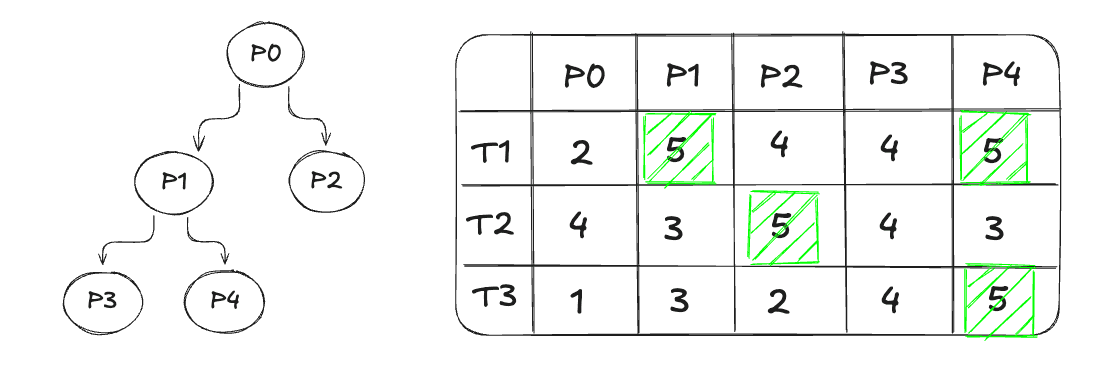

Fig 2: Candidate Selection

GEPA uses a Pareto-based strategy for selecting which candidate prompts should continue evolving. The idea is best understood through the figure above. Each prompt (P0–P4) has scores across several tasks (T1–T3). Higher scores mean better performance. Below are the steps in this selection strategy;

Identify the best prompt for each task

For every task, we look for the prompt that achieves the highest score.

T1 → P1, P4

T2 → P2

T3 → P4

This gives us a set of task-wise winners.

Remove strictly dominated prompts

A prompt is strictly dominated if there exists another prompt that performs at least as well on every task and strictly better on at least one.

In the example:

P1 performs best on T1, but P4 matches P1 on T1 and outperforms it on the other tasks.

Therefore, P1 is strictly dominated by P4 and is removed.

The surviving prompts are those that are not dominated by any other prompt. These are the candidates worth exploring further because each of them represents a different tradeoff across tasks.

This strategy tends to pick “specialist” prompts i.e. candidates that are uniquely strong on at least one task. The hope is that combining their strengths across iterations leads to better overall prompts.

However, the example also shows a limitation:

P4 performs consistently well across all tasks, yet it is not chosen by Step 1 because it is not the top performer on T1 or T2. It is a “generalist” prompt with solid, balanced performance, but the selection method may ignore it.

This illustrates that Pareto-based selection is only one way to rank candidates. It is useful, but not always ideal depending on the optimization goals.

Implementation & Results

Let’s take a look at how we optimized the prompt for creating plans which a retrieval agent would execute. Below is an example data point in our dataset:

For each user query, we have a gold plan and the reasoning behind it. We found that annotating the human reasoning behind each plan generates high quality feedback from the LLM judge. The goal from each data point is to convey how we want the plans to look and what’s the logic behind it. Ideally, the logic from each data point should get encoded in the final prompt.

For this task we used 75 labelled samples. The input consists of user query, date, employee details of the person asking the question, employee details of the person to which the question is asked and enabled data sources. To keep things simple, we didn’t include other information like memory instructions and custom instructions.

The output for this task is just a list of steps in the plan. For evaluation, we used LLM as a judge, which gave natural language feedback. For scoring the generated plans, we initially used a 0/1 scoring, where 1 means the generated plan totally aligns with the gold plan. But this scoring was too strict and the optimization process was never able to evolve.

In order to make the scoring a bit relaxed we decided to use LLM to give a score between 0-5 and defined what each score meant. Here is what an example feedback looks like in our case:

In the above example, the generated plan might be right and still work, but it’s not what we want. It’s too granular and iterates over each data source and also has synthesis steps. For such queries, we don’t want to infer any sources and the plan should be to just look at authored docs by the person and the docs in which XYZ participated. It is up to the agent whether each step needs more search calls or not. From this feedback, the hope is that the improved prompt will focus on how to decompose tasks, how to not split the steps for each data source and not infer any data source when not trivially inferrable, not to include any synthesis steps.

For the optimization loop, we used a minibatch size of 10, and generated 5 candidates per proposal (to minimize variance). We used GPT-5 with ‘medium’ reasoning for candidate proposals. This configuration gave us the best results and the plan generated by the final prompt scored an average of 4.1 (on a scale of 1-5) after 15 iterations. We have attached the starting and optimized prompt in the appendix.

Key Learnings

Iterate on the error - candidate prompt loop: The whole system depends on a single step: look at the errors from the current prompt, then propose an improved prompt. If this step fails, the entire optimization breaks.

To keep it healthy:

iterate on the proposal prompt itself until it consistently produces sensible edits

verify that judge feedback is specific and actionable

inspect generated candidate prompts to make sure they stay within your intended design space

High quality feedback matters: For open-ended tasks (e.g., plan generation), all learning comes from the judge’s natural-language feedback. Simply comparing an output to ground truth is not enough; the model needs reasoning. Annotating examples with brief rationales produced much better and more constructive feedback in practice, which in turn led to more meaningful prompt improvements.

Using a stronger model for candidate proposals: In our case, we use gpt-4.1 for creating plans. Initially in the optimization loop, we used gpt-4.1 for proposing new candidates; thinking that models from the same family might help. But, when switching to gpt-5 for candidate proposals, we observed better prompts.

Generating multiple candidate prompts helped: Generating several candidate prompts per step reduced variance and increased the chance of discovering a genuinely better prompt.

Dataset must be diverse and trustworthy: If the optimization loop is meant to learn from data, the training set must reflect the variety of cases seen in production. Also inspect samples individually. A single poor data point won’t derail the loop, but it can introduce misleading feedback or distort the candidate proposals.

Appendix

Seed Prompt:

Optimized Prompt: